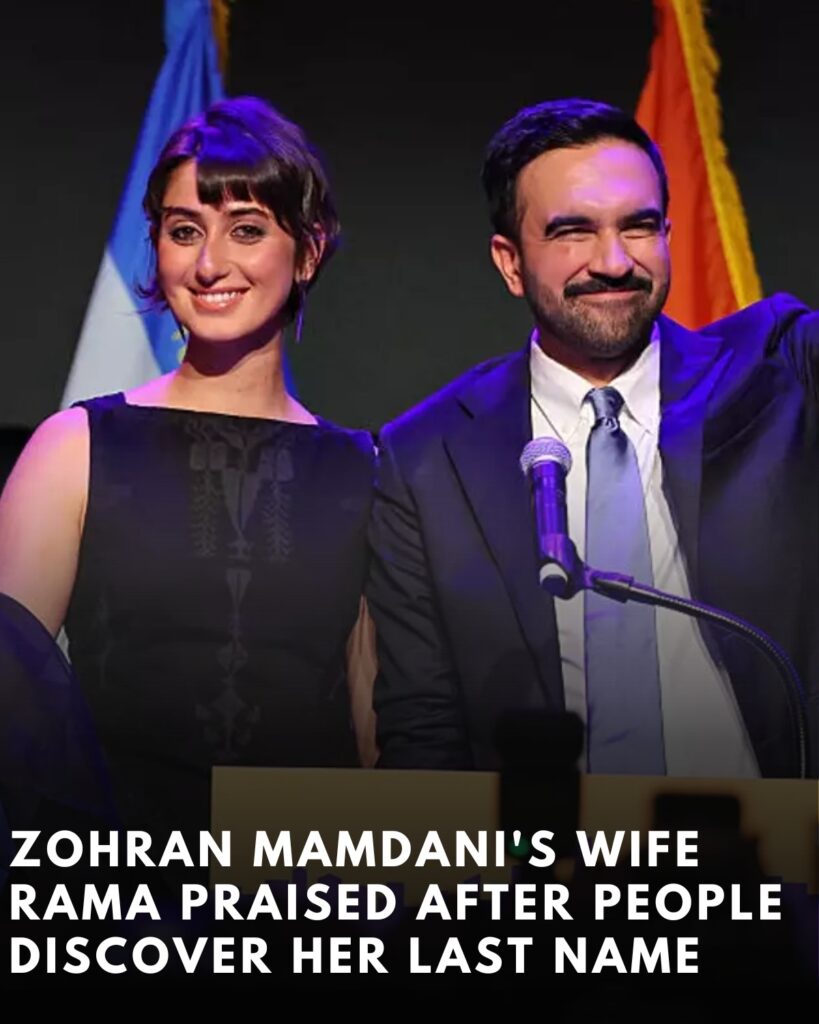

New York’s incoming first lady, Rama Duwaji, became a focal point of online conversation in the days after Zohran Mamdani’s upset victory, with social media users poring over biographical details, re-watching his election-night remarks and, notably, clocking that she uses her own surname rather than adopting her husband’s. The scrutiny has produced a wave of interest and largely positive reaction around the 28-year-old Syrian-American artist, whose profile and work long pre-date her husband’s political rise but had, until the election, remained largely within creative circles. In an acceptance speech that has already been widely rebroadcast, the mayor-elect looked over to his wife at the rally and said: “And to my incredible wife, Rama, hayati [my life]. There is no one I would rather have by my side in this moment, and in every moment.” The affectionate aside, delivered as he thanked campaign staff and supporters, has been repeatedly clipped and shared, helping to introduce Duwaji to a much broader audience.

Public curiosity has quickly fixed on who Duwaji is in her own right. Profiles compiled after the election set out a straightforward biography: born in Texas to Syrian parents, raised partly in the Middle East, a graduate in communication design from Virginia Commonwealth University, and a working illustrator, animator and ceramicist based in Brooklyn. Her client list is unusually blue-chip for an artist of her age, with commissions and features across major newsrooms and brands, including The New Yorker, The Washington Post, the BBC, Apple and Tate Modern. She moved to New York in 2021 to continue her practice and has exhibited or contributed work internationally.

Her relationship with Mamdani, a democratic socialist who moved from the New York State Assembly to City Hall by defeating former governor Andrew Cuomo, is recent but not rushed. The couple met on Hinge, began dating in 2021–2022, got engaged late last year and married in a civil ceremony earlier in 2025, sharing images from those milestones to their private social circles and public feeds. In a caption picked up by outlets covering the race, she posted a simple line after one of his victories: “Couldn’t possibly be prouder.” The pair kept a relatively low-key public posture during the campaign, with Duwaji rarely speaking on political stages and declining to become a surrogate, a choice consistent with the way she has run her own practice—visible through the work, not speeches.

The online conversation since election night has followed familiar patterns when a political spouse becomes newly visible: a surge of interest in professional background and nationality; a reassessment of public images taken before the campaign; and attempts to place the individual on issues based on prior creative work. In Duwaji’s case, her portfolio offers accessible clues. Much of her past illustration and animation has a political or humanitarian thread, exploring Arab and diaspora identity, immigration enforcement and the experiences of civilians in conflict zones. Commenters have resurfaced examples, including a storyboard produced for a feature about survivors of Israeli strikes and pieces reflecting on displacement and resilience. While most of that catalogue ran before Mamdani’s citywide race crystallised, it has fed into a perception that New York’s next first lady brings a defined artistic lens to the ceremonial and community-facing work she will inherit at City Hall.

Attention has also turned to the couple’s presentation and the cultural markers threaded through Mamdani’s rhetoric. The Arabic term of endearment in his victory speech, “hayati”, resonated far beyond Arabic-speaking audiences once outlets translated the phrase. Supporters argued that the line, alongside his broader multilingual outreach during the campaign, was a continuation of an approach that foregrounded the city’s immigrant identity. The effect was to place Duwaji not merely as the subject of praise from the podium but as a figure woven into the larger story Mamdani’s campaign told about New York—plural, multilingual, and, in their framing, confident about public expressions of heritage.

Another line of commentary has focused on her name. As media profiles circulated, many readers and viewers noted that she uses her own surname—Rama Duwaji—rather than taking her husband’s. In the United States and the United Kingdom, retaining a birth surname remains an established option at marriage and has long histories in feminist organising and in communities where name changes are culturally uncommon. The renewed attention around Duwaji’s surname has prompted swathes of social media posts applauding what they view as a straightforward, modern choice that reflects professional identity. While it is hardly new—activists have advocated for it since the nineteenth century, and many women across cultures never change their names—the election’s high visibility means the conversation has broken into mainstream feeds, often framed by users as a small but telling detail about how the couple present themselves.

Beyond biography and symbolism, the practical question is what kind of first lady New York will have in January. There is no statutory job description; first ladies of the city have historically taken on a blend of advocacy, philanthropy and soft-power convening. At 28, Duwaji is set to be the youngest to hold the role, which inevitably draws comparisons with previous occupants who used the platform to highlight particular issues—from literacy to mental health to community-based violence prevention. Early coverage suggests she will continue to prioritise artistic practice even while stepping into ceremonial duties, and the portfolio she brings—storytelling about vulnerable communities through visuals—offers a ready-made set of themes for City Hall partnerships. That could mean collaborations with public libraries, cultural institutions, youth arts programmes and immigrant-serving charities, although no formal slate has been released and aides have been cautious about projecting too much onto a transition still being built.

The couple’s personal story has been stitched into this emerging narrative. Public remarks from election night and earlier campaign moments depict a partnership where Duwaji’s support is both personal and professional. Mamdani’s “hayati” line has been the viral soundbite, but his campaign had already positioned her as an independent artist whose career stands on its own. That two-track presentation—mutual support without subsuming identity—has fed the tenor of many reactions praising the pair, with users drawing a connection between the surname detail and the content of Duwaji’s work about identity and belonging. The election’s symbolism—a Muslim, millennial mayor who emphasises immigrant New York—has only amplified that reading. For supporters, it is all of a piece; for critics, it is branding. Either way, the facts are not in dispute: Duwaji is an established creative who chose continuity in her professional name and has been brought into the centre of a national-level political story by her husband’s win.

There are, inevitably, questions about how the line between art and politics will be navigated once the administration takes office. Duwaji’s portfolio includes work touching on polarising issues—immigration enforcement and the Middle East in particular—that New York’s civic institutions engage with constantly and carefully. Profiles have noted her pieces on ICE and Gaza, and while nothing in the role of first lady obliges her to adopt a public political posture, the reality of modern public life is that past work will continue to be read through political lenses. Strategists around past mayors have handled that tension by keeping the first lady’s advocacy distinct from city policy apparatus while coordinating on events and fundraising for non-profit partners. The current transition has not set out an approach, but the attention on Duwaji’s art makes this a live question for City Hall’s communications team.

For now, the public record around the couple’s timeline is uncomplicated. They are recent newlyweds who met by app, married at City Hall early in the year and have marked key campaign milestones with snippets on social media. Duwaji’s Instagram output remains largely focused on her practice rather than campaigning and, even when she has celebrated her husband’s wins, the messages have been brief and personal rather than programmatic. The description tallies with reporting that she deliberately avoided becoming a surrogate speaker during the race and stuck to the background at major set-piece events, surfacing most prominently when the votes were counted and the victory stage required a family tableau.

That the discovery of a surname could generate such traction online says as much about contemporary political consumption as it does about the people involved. Election nights deliver a glut of images and micro-moments; audiences cluster around symbols that feel legible—language choice, family presence on stage, clothing, and, in this instance, a name appearing on chyrons and captions that is not the same as the candidate’s. In New York, a city where hyphenations, double-barrels and non-changes are common, the response has nonetheless been telling. For many who posted, it read as a simple signifier of professional continuity and self-definition, a point made not with a podium statement but with the decision to continue signing work as she always has. The broader social context is straightforward: in both the US and UK, keeping a birth name has become a well-established marital choice, and the practice is commonplace across numerous cultures. The fresh interest here stems from scale, not novelty—the scale that attaches to a mayoralty and the viral nature of a line like “hayati” echoing across feeds.

As the transition proceeds, the city will move from the theatre of an election night into the practicalities of governing, and Duwaji’s prominence will likely narrow to a steadier rhythm of appearances and projects. The art world’s view, however, is unlikely to recede; clients and collaborators now find their colleague the subject of mainstream headlines, and the work that drew those clients—stylised, narrative-driven pieces about displacement, family and community—has new visibility. Whether she uses that platform to convene arts education initiatives, to tell stories from immigrant New York, or to keep a strict line between studio and City Hall, the early weeks have made one thing clear: much of the public is judging her on her own terms. That judgement is not based on a speech penned for her or a campaign surrogate file; it is based on a portfolio, a name on a credit line and a moment on a victory stage where her husband said what millions then repeated back online, in translation and with approval.

What follows will be less memeable. New York’s ceremonial roles are often weighty without being loud, and it is in that space—gallery openings in the boroughs, school visits, meetings with small arts non-profits, immigrant community fundraisers—that first ladies build durable reputations. Duwaji’s experience suggests a comfort with those rooms and a set of interests that align naturally with them. The public interest in her name will not endure at its present pitch. But the attention has already performed one function: it has introduced a young artist to the city she will represent, not as a political prop but as a defined professional with her own voice and choices; and it has done so in language that was hers long before a mayoralty, the language of a surname kept, a practice maintained, and a body of work that people are now seeking out for themselves.