The MRI experiment endures not for shock value, but because it blended curiosity, intimacy, and scientific correction. In the early 1990s, MRI technology was still seen as a cold diagnostic tool, not a way to study everyday human function.

Ida Sabelis and her partner Jupp took part at the request of a researcher friend, not for attention. Their goal was simple: test long-held anatomical assumptions using direct observation rather than inherited diagrams.

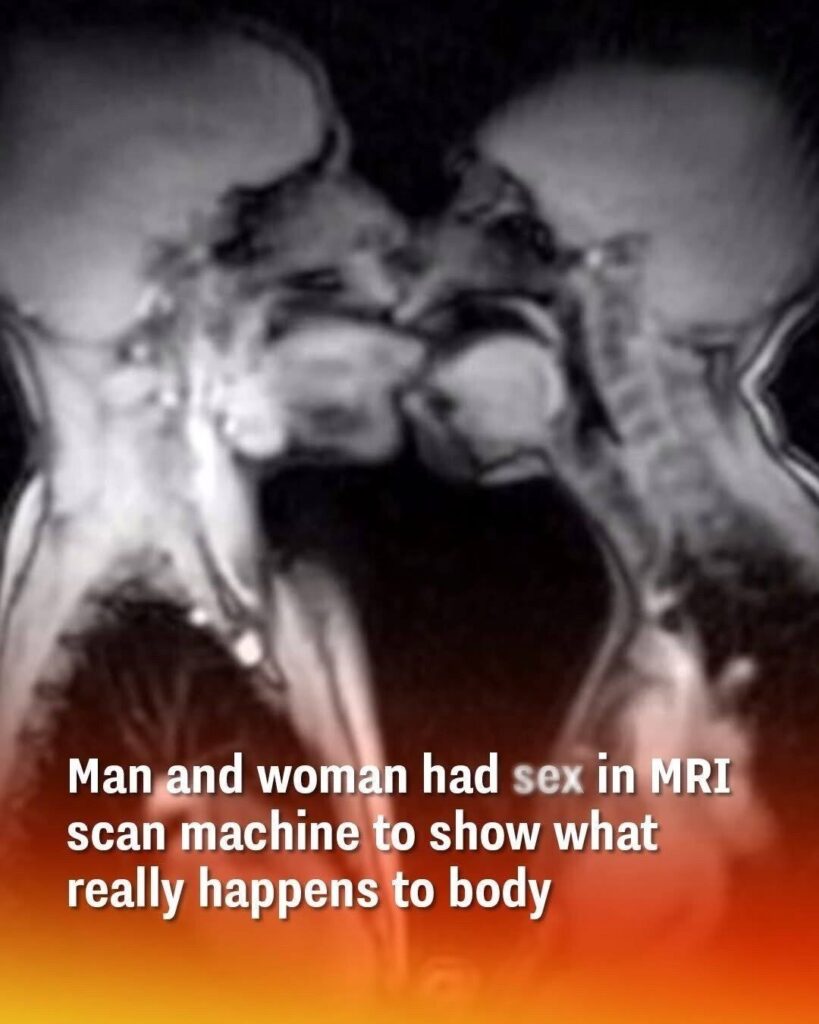

The setting was far from romantic. Early MRI machines were cramped, loud, and slow, requiring stillness and patience. Technical constraints dictated positions, removing any sense of spectacle and reinforcing the experiment’s seriousness.

Scientists focused on spatial anatomy, not intimacy. The awkward environment stripped away drama, allowing the act to be reframed as a legitimate subject of medical inquiry rather than a taboo curiosity.

The resulting images challenged centuries of belief. Traditional anatomy, influenced by Renaissance drawings like Leonardo da Vinci’s, portrayed the vaginal canal as straight. The MRI scans revealed curvature and adaptability instead.

This finding reshaped understanding of anatomy as dynamic rather than static. It showed how the body responds to interaction, with implications for medical education, comfort, and discussions of physical compatibility.

Published in the British Medical Journal, the study drew widespread attention. Readers responded not to sensationalism, but to its humanized science and clear correction of a deeply rooted misconception.

For Ida, the lasting impact was unexpected. What felt like a small favor became a meaningful contribution to knowledge. The study remains a reminder that even familiar aspects of the body deserve fresh observation and evidence-based understanding.